he myth of this “Golden Age” of the martial law years has been so thoroughly debunked in social media even the Marcos campaign has virtually dropped it.

Instead of a vote-magnet it became a deadweight to carry around. Everytime they mentioned martial law, it always triggered a blizzard of follow-up questions so difficult to answer that Junior just decided to skip all debates altogether where these questions tend to get asked.

Unfortunately for him that, too, backfired because as the saying goes, “if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.” His absence at the podium did not stifle talk about his father's world-class kleptocracy as only another authentic Marcos like him can embody.

After the latest BIR pronouncement on the unpaid Marcos estate tax liability, there are 203-Billion even more reasons not to forget what the phrase “Marcos legacy” means.

Of course, the BBM apologists protest that we should not be raking a dead man over the coals—Ferdinand Marcos, the senior, is now a wax statue that used to lie in a glass coffin in Batac, Ilocos Norte before finally being interred amid tumultous protest at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

Admitted. But these are the same people doing the same thing to the long-dead Jesse Robredo, minus the credibility in the accusations. That Marcos stole money is undisputably proven by the fact that the government has recovered some of it, albeit a mere pittance of what remains to be recovered yet.

On the other hand, the allegation that Leni’s highly-respected late husband stole the Supertyphoon Yolanda calamity fund is disproven not only by fact-check but by sheer logic: Jesse Robredo was long-dead BEFORE Yolanda even began as a tropical depression. The BBM people simply have to learn how to lie BETTER if they aspire to dent the unreproachable integrity of the lady in pink by villifying her dead husband. Secretary Robredo died leaving behind no derogatory record, only the support and adulation of the Camarines people who overwhelmingly voted his widow into office TWICE to Congress and the vice presidency. Leni IS Jesse Robredo's legacy.

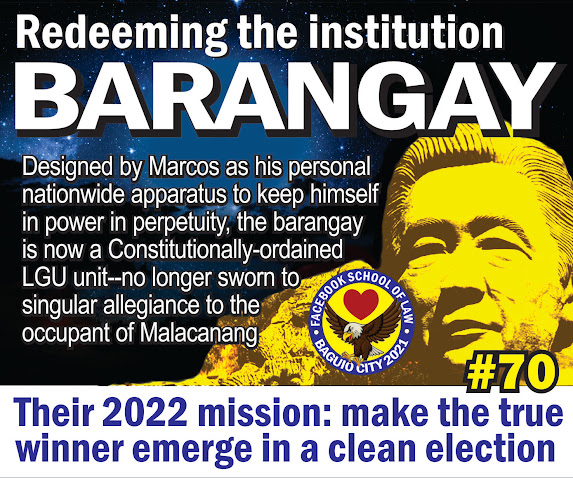

So long as we're in the subject of legacies, maybe there IS one legacy even I would concede to the deposed dictator. I think the biggest oversight made by the BBM pipol is this: they forgot to brag about the BARANGAY.

In a cynical sense, Ferdinand Marcos invented that institution in 1974 by officially renaming the Spanish colonial-era “cabeza del barrio” into the “barangay captain” (later “punong barangay”).

By all political calculations, the draft 1973 Constitution would have never passed muster in a genuine referendum. So what Marcos did was order the convening of “citizens assemblies” all over the country. He then had photographs of them taken while they raised their hands, as though enthusiastically responding to some question. Many living eyewitnesses swear the question was, “sinong may gusto ng sardinas, ‘taas ang kamay?” because thousands of boxes of sardine cans were distributed at these citizens assemblies all over the country at the same time.

When the validity of the 1973 Constitution was challenged in the so-called “Ratification Cases” before the Supreme Court, the rubberstamp SC back in the day admitted those photographs as, “evidence” that the constitution was formally “ratified.” By informal assemblies? Go figure.

Marcos saw and quickly exploited the effectiveness of a nationwide network of loyal martial law implementors who will do all his biding for a can of sardines. So he spent the next several years strengthening the institution. The barangay captain—or “bokap” for short—was elevated to the status of a public officer, and not just an ordinary one but a “person in authority.”

Keep this in mind because if you ever figure in a physical confrontation with your bokap, you’ll be facing the charge of “direct assault”—a serious offense—and not just the less serious “physical injuries.”

Even as a lawyer, Ferdinand Marcos’ legendary legal chops is suspect. The Katarungan Pambarangay under Presidential Decee 1508 is uniquely looked upon with skepticism throughout the whole world’s legal community (seriously) in its perversion of the sociocultural-powered mediation process of the Lupon Tagapamayapa.

Although not really a court with judicial powers, the commonly-misnamed “Barangay Court” handles DISPUTES, not cases. It pioneered the idea of a collegial body, called “Pangkat ng Tagapagkasundo,” brokering an amicable settlement between disputants using weaponized embarrassment as counter-incentive. Do you ever wonder why you lodge a complaint against somebody with the barangay captain of the barangay where your “enemy” lives? Why not in YOUR own barangay, which makes more sense? The proceedings are presided over by your enemy’s barangay captain who is deemed to be the one with moral ascendancy over your “enemy” and can presumably lean on him harder enough to capitulate.

It is counter-intuitive to the idea of a “home court advantage.” You must trust that the barangay captain runs his community’s affairs based on the "honesty system" which can be a long stretch in many places You have to super-extend that trust to believe that universal reason and fairness would deter the barangay captain and HIS CONSTITUENT from conspiring to screw you behind your back!

It is a totally naïve setup that made sense only in the twisted value system of Marcos, best summarized by that enduring mantra of corruption, “lahat puwedeng idaan sa usapan.”

There are 42,046 barangays throughout the Philippines. They are not only the frontliners in the delivery of many ministrant functions of the government, they are literally the human face of the State. In remote countryside villages unreached by regular transportation, they are often the only interaction the ordinary citizen ever has with the government. Name any government program, these barangay officials are likely the ones implementing it: Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino program, Bayanihan “Heal-as-One” ayuda programs—anything that entails dispensing money, benefit or favor, it is the barangays that are in charge of doing it.

Throughout martial law, Marcos used the barangays as implementors of all his "do good" policies and show window programs--Masagana 99, Gulayan ng Bayan, the 'Green Revoution', Mag-impok sa Bangko campaign, Pulong Pulong sa Kaunlaran (forerunner of the Kapihan format), etc. If it was the stuff of propaganda and public relations, the barangays were in the thick of it.

Marcos' formula for maintaining martial law was simple. For all the draconian measures he needed to do that "gentle-sloped" into the mass atrocities and human rights violations we now know of, he used the MILITARY.

But for all the deodorizing activities meant to paint a smiling face to his dictatorship, he used the BARANGAY. Is it any wonder, therefore, that today this hoodwinked class of Filipinos only remember "the true, the good and the beautiful?"

Don’t get me wrong. There are many fine barangay officials. Institutionally, the barangays have come a long way from a nationwide Marcos apparatus singularly loyal to promoting the “New Society” to now being the formal basic local government unit (LGU).

The barangay is explicitly mentioned in Article X, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution. They no longer owe their existence to a Marcos presidential decree.

Pursuant to this, Congress subsequently enacted Republic Act 7160, or the Local Government Code of 1991. This landmark legislation fully ‘professionalized’ the barangays, laying out guidelines for how they can promulgate their own ordinances--even generate their own sources of revenue.

THAT is progress, because now the barangays are no longer a personal political machinery sworn to singular allegiance to Marcos. They are now part of the civil service and covered by the non-partisanship restrictions of our election laws. So they can no longer be exploited by political parties—including incumbent ruling parties or coalitions—for campaign purposes.

In theory.

In practical terms, barangay officials are still human, too, and they still succumb to padrino dynamics. The last barangay election was held way back in 2018. So if you are “BBM people” you’re thinking these incumbent set were all elected during the Duterte Administration—not exactly a Marcos-friendly demographic.

The present set of barangay officials have served the entire duration of President Duterte’s term, but for the most part as antagonists. If there are two things that characterize corruption under the Duterte regime, it is centralization and negotiation. Few public works projects, if any all, are still implemented “by administration” these days. Most of them are farmed out to a pool of accredited public works contractors, by fractured negotiated contracts. The illegal commissions--kickbacks--from these projects only kick in one direction: upwards to mayors, governors and congressmen—including the greediest ones of the caretaker variety who demand 40 percent.

In short, in the division of ill-gotten spoils, barangay officials have been completely cut out, for their own good and ours. No single group of people know, understand and suffer the effects of corruption more than they. Over time, many of these grassroots officials—perhaps the last remaining species of pure public officers—have countermorphed from being Marcos’ henchmen and women to now being the biggest most consequential sector to power genuine change.

All claims to the contrary, it is my firm belief now that the barangays can no longer be bought--at least, not with a can of sardines.

Of course, some politicians still try to buy them with ambulances and tarpaulins--whose only use is to remind people that this disgusting congressman still looks at barangays the same way Marcos did: "patay gutom" errand slaves chasing after a can of sardines.

I know one who runs around Benguet doing this, because he's been told that iBenguets are too polite, too naive, too submissive and too subservient to say NO to him.

But, personally, I think he will get his overdue comeuppance on May 9, as will anybody else trying to channel Ferdinand Marcos Classic.

And that is STILL bad news for Ferdinand Marcos 2.0**